Let’s clear this up at the very start: the famed image of the black hole was the product of a team of 200 individuals all over the world. What Katie Bouman exclusively contributed was the algorithm required to form this image. She led the development of a computer program which eventually put all the pieces together. We’re not saying Katie Bouman was the only person to forward this achievement (she wasn’t even the only woman), but she was an instrumental part of the process.

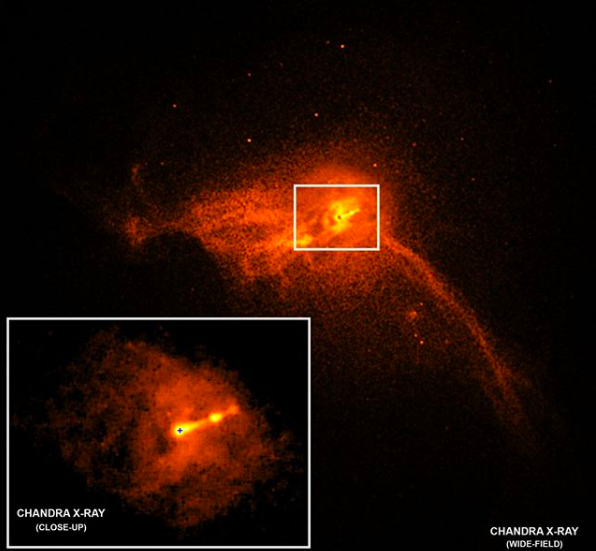

Photo from NASA

(The first-ever photo of a Black Hole has just been revealed)

Why was her algorithm so important? Well, it’s because the object we refer to as an image isn’t that in its strictest sense. People assume that the image of the black hole was taken with some sort of camera when in actuality it is the data from 8 different telescopes weaved together with Dr. Bouman’s algorithm.

Dr. Bouman explains it as such:

The law of diffraction says that if you know the resolution you need to achieve, and the wavelength you are observing at, then you can figure out what your telescope size should be.

We needed an Earth-sized telescope, and obviously we couldn’t build an Earth-sized telescope dish. Instead, we took eight different telescopes from all around the world that were built for other purposes, and we joined them together to act as one dish.

That’s what the Event Horizon Telescope is.

No single telescope would be powerful enough to capture the black hole by itself (it is 500 million trillion km away) as it would have needed to be around the size of Earth. So the team behind this discovery thought up the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT): a network of 8 telescopes linked together. The EHT extracted the necessary data through interferometry. That data was then stored in hundreds of hard drives and flown to Boston (USA) and Bonn (Germany) for processing.

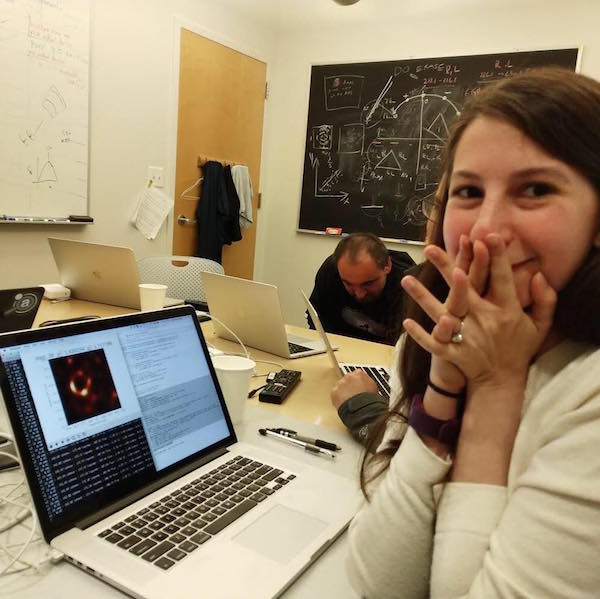

Photo from Katie Bouman

She further elucidates:

No telescope actually takes a picture. What happens is, the light from the black hole travels 55 million light years and then every dish collects a single stream of the light that it sees at the same time.

That’s recorded onto these hard drives. We can’t send that data over the internet because it’s way too big — [the hard drives are] sent on airplanes to a central location, where they’re computationally processed.

But it’s incomplete.

The process of imaging is taking the incomplete information that we get from a couple of places on our virtual telescope, and trying to fill in all the missing information to get the picture an actual Earth-sized telescope would have produced.

That is a hard problem.

Take your rightful seat in history, Dr. Bouman! 🔭

Congratulations and thank you for your enormous contribution to the advancements of science and mankind.

Here’s to #WomenInSTEM!

👩🏻🔬👩🏾💻👩🏼🏭👩🏿🏫 https://t.co/3cs9QYrz9C— Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (@AOC) April 10, 2019

(Filipino-Made App Wins Big in NASA)

The series of algorithms which Dr. Bouman spearheaded essentially converted that data into the image we have now. The technical explanation is that “multiple algorithms with different assumptions built into them attempted to recover a photo from the data.” She describes it like this:

There’s an infinite number of possible images that could have been created from the sparse measurements that we took. The goal of imaging is to find the image that not only reconstructs and matches the data that we measured, but also is the one that is most likely.

We have to impose some information about what the image should look like in order to recover that image. Some stuff that we impose is natural and easy — we know that light is positive. You can’t have negative light.

Other things we might impose would be how smooth the image is. You wouldn’t expect an image of a black hole to look like the white noise you get when you pull a cable out of your television.

You really don’t want to accidentally tell our imaging algorithms that, for example, “Oh, what is likely is this ring shape,” because then we just recover that ring back, and we’ve learned nothing.

To avoid shared bias, we split ourselves into four different teams that had different focuses and different kinds of algorithms. We worked separately for a month, not talking to each other about anything.

Then after one month we all gathered together in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and we put all the images up on a screen at one time. I think that was the most amazing moment, because even though each of the other images had different underlying assumptions and looked different, this ring appeared in all of the images.