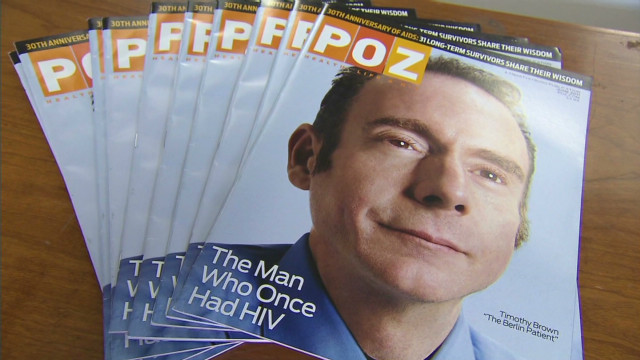

12 years ago Timothy Brown became the first person in history to be ‘cured’ of HIV, the infection which often leads to AIDS. Scientists and medical professionals have since then made several attempts at duplicating this success. It’s only now, with the so-called ‘London Patient’ (who wishes to remain anonymous), that a repeat of the long-term remission looks to finally be happening.

(Let’s break the stigma: 10 misconceptions about HIV and why they’re wrong)

Both patients were cured of the virus after receiving a bone marrow transplant. It had not been intended to address their HIV infection but was needed for their respective kinds of cancer. After Brown’s recovery from HIV over a decade ago, many tried to repeat the procedure with other HIV-infected cancer patients. Unfortunately, the results were always the same: the virus would either return after some months in remission (usually 9) or the patient would succumb to cancer.

Because of this, many believed Brown’s case to be a fluke. There was concern that the cure could only be replicated if Brown’s circumstances were replicated as well. The problem with that was that Brown underwent “a massive amount of destruction to his immune system” due to harsh immunosuppressive drugs. The transplant effected dangerous complications which nearly led to his death. For a long time, the medical community was under the assumption that a ‘near-death experience’ was the only way for the procedure to work.

Now, the London Patient stands as a testament against that. It has been nearly 2 years since he stopped taking anti-HIV drugs in September 2017 and the repeated analysis of his blood tests have been declared HIV-free. Because he had been taking the standard immunotherapy drugs beforehand, there were no life-threatening effects like Brown went through. Scientists, then, were called to look at the similarities in the cases.

A cake given to Brown in celebration of the 12 years he has been cured

They realized that both patients received stem cells from a donor with a rare genetic mutation of the CCR5 gene which essentially makes them resistant to HIV. Aside from curing their cancer, the transplant served to replace their vulnerable cells with newly immune cells. Scientists are now tracking 32 similar cases of HIV-infected individuals receiving bone marrow transplants. One of them, coined the ‘Düsseldorf Patient’, has been off anti-HIV drugs for 4 months now.

(Here’s a List of Clinics in the Philippines That Offer Free HIV Testing)

Despite that, there seems to be a consensus that bone marrow transplants are not a viable cure for HIV infection. There are clear risks that stem cell transplants inherently hold, and there are even more risks when bringing the CCR5 gene into the equation. It is not a sustainable cure for HIV with so many externalities at play. But it does bring hope to the table.

Anton Pozniak, the president of the International Aids Society, stated:

Although it is not a viable large-scale strategy for a cure … these new findings reaffirm our belief that there exists a proof of concept that HIV is curable. The hope is that this will eventually lead to a safe, cost-effective and easy strategy to achieve these results using gene technology or antibody techniques.

Professor Ravindra Gupta, who authored the paper on the London Patient, suggests that this paves the way for the editing of the CCR5 gene as a viable cure. He explains:

A field was generated as a result of the Berlin patient looking at CCR5 gene-editing. You may have heard of the Chinese babies that were having experimental knockout of that particular gene. But, CCR5 gene-editing in infected patients was a justifiable goal. What this second case says is this is a bonafide research target and probably the most promising we have for any HIV cure.

The significance of this success is another step towards that long-awaited solution to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. While the treatment of antiretroviral drugs has certainly been a milestone in this battle, it can’t end there. A definitive cure, one that leaves no one out on the fringes, should remain the ultimate goal.

Do you have anything to add to this story?

Sources: The Guardian, NY Times