The emergence and establishment of the human rights regime arose heavily as a response to the horrifying events of World War II, particularly from the so-called ‘Final Solution’ that murdered six million Jews, Gypsies, and Slavs in the extermination camps of Nazi Germany. With the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights serving as the heart and soul of this regime, it serves to promote and protect human rights – universal, fundamental, indivisible, and absolute entitlements humans possess by virtue of being human. It has provided a comprehensive code for its member states as to how they should govern internally. These agreed upon rights cover both civil and political rights extending to economic, social, and cultural rights. The Philippines, as a signatory to this declaration, expressed its commitment in recognizing and observing the dignity and worth of every human being within its territory. Accompanying the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the current 1987 Constitution of the Philippines, particularly in the Bill of Rights, declares the rights and privileges of every Filipino citizen that the constitution must protect at all cost. Furthermore, the constitution calls for the establishment of an independent National Human Rights Institution (NHRI) which came in the form of the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) by virtue of Executive Order No. 163 that mandates it to conduct investigations concerning violations of political and civil rights.

With all these agreements and institutions in place, human rights may have become the international norm. However, in the political arena, several theoretical and practical debates have sprouted and have continued to tackle the human rights regime from the time of its emergence.

In the Philippines and its current administration, the discourse on human rights have never been as boisterous ever since the former president Ferdinand Marcos’s authoritarian rule that was marred by rampant human rights violations. President Duterte’s hallmark ‘War on Drugs’ has recorded an estimated 7,000 extra-judicial killings. In addition, from the countryside, the homes and alternative schools built from the initiative of indigenous groups in Mindanao called ‘Lumads’ are being militarized and, their leaders and teachers are being slain by agents from the Armed Forced of the Philippines. Even further, the president himself even threatened to bomb the schools upon his order. The recent declaration of Martial Law in Mindanao as a response to terrorist threats inMarawi also has a share of reported human rights violations wherein some evacuees were tortured, psychologically interrogated, and stripped in evacuation centers. In such context, the issue of human rights is inevitably placed under the spotlight for comprehensive scrutiny.

Human rights, despite its prominence, have been criticized in its philosophical foundations of universalism – that characteristic of human rights that assert that they belong to human beings everywhere, regardless of race, religion, and other differences. However, Communitarians, for example, take a relativist stance claiming that rights should not be universal, but rather local and particular on the basis that individual experiences are shaped by his immediate milieu and cannot be separated from the social context. They argue that political and cultural context must be taken into account in qualifying human rights and moral values.

In its pragmatic aspect, the question that stands out is whether if human rights should be restricted in times of threats such as that of terrorists. On the camp of those for the restriction of human rights and basic freedoms, they argue that curtailing human rights and freedoms is justifiable on utilitarian grounds; that is, if it produces the greatest good for the greater number of people. Similarly, supporters of this camp advance the doctrine of ‘dirty hands’ which distinguishes between public morality and private morality. They argue that leaders may do what is not right in the name of public morality even at the expense of private morality. In contrast, supporters of human rights take a clear stand that freedom is a fundamental value and should never be a question of trade-offs. Rather, the questions should always concern the intrinsic rightness and wrongness of certain actions. While they recognize the political inconveniences upholding human rights may incur, they fear and warn that when governments increasingly treat morality in terms of trade-offs, it slides down towards authoritarianism.

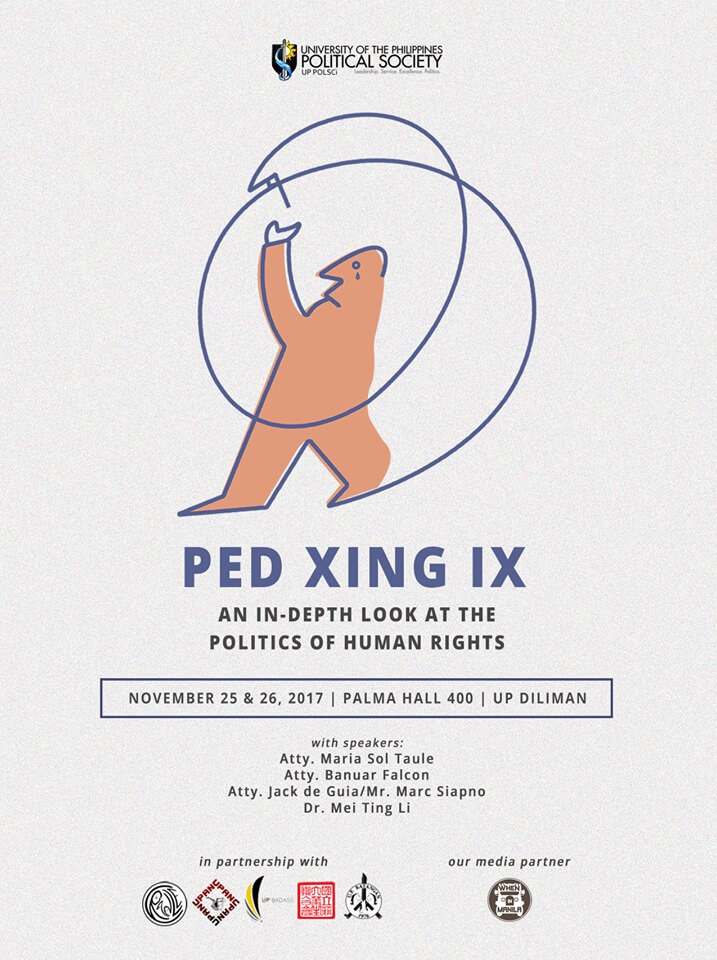

Given these debates and the pressing conditions we are in, the University of the Philippines Political Society (UP POLSCi), in partnership with UP Anna Na Cagayan, UP Badminton Assocition, UP Batangan, UP Chinese Student Association, UP Children’s Rights Advocates League, and media partner wheninmanila.com, will hold its ninth Ped Xing Conference with the theme “Ped Xing IX: An In-depth Look to the Politics of Human Rights” to primarily introduce and forward the discipline of Political Science to the youth, and also equip high school students with the basic skill of critically analyzing and understanding relevant political issues through educational discussions and competitive platforms where students will express their abilities and knowledge of politics. The Ped Xing IX conference will be held on November 25 – 26, 2017 at PH 400, Palma Hall, University of the Philippines – Diliman, Quezon City.